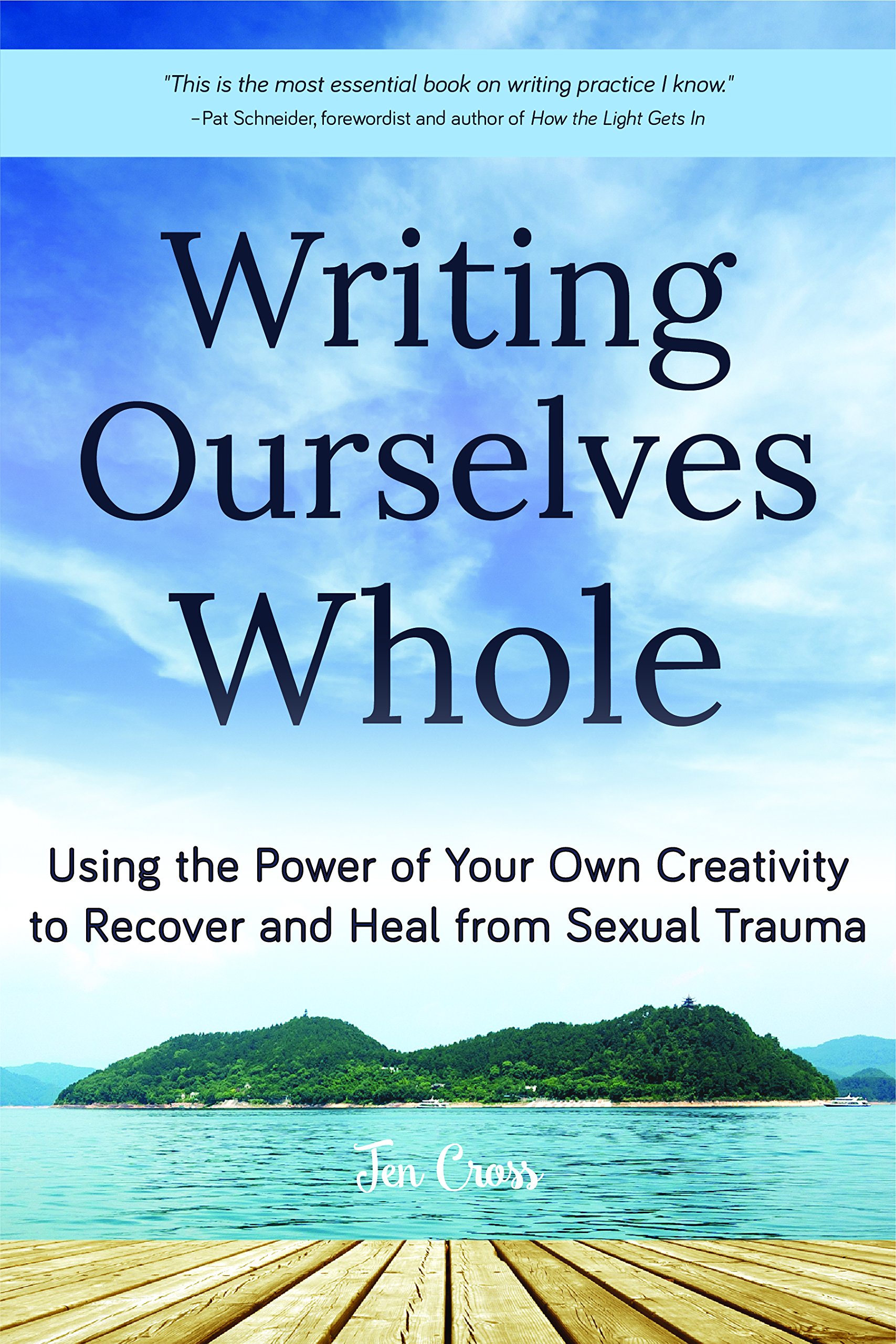

(Good morning, good morning! While I’m away, I wanted to share with you some pieces from my book, Writing Ourselves Whole: Using the Power of Your Own Creativity to Recover and Heal from Sexual Trauma, which is coming out next month! I’ll post one of these a week, on Friday mornings. Be easy with you, ok? And please keep writing…)

From “introduction: how to restory”

From “introduction: how to restory”

I started journaling in 1993, when I was twenty-one years old and breaking away from my stepfather after nearly ten years of ongoing sexual, psychological, and physical abuse. As often as I could, I took refuge in local café, where I bought a large, dark roast coffee, and popped a tape into my portable cassette player—Ani DiFranco, Erasure, Zap Mama, The Crystal Method—slid my headset over my ears, folded the notebook open to a new page, uncapped my pen, wrote things I thought I’d never be able to say out loud. I spent years doing this, my butt planted in a wooden chair in some coffee house or other in Northern New England or around San Francisco. This is the way I found my tongue again. I wrote through the numbness that kept me protected—through writing I could feel the sadness, despair, depression, rage. The emotions had a weight and a shape once they found their way into words, whereas, inside me, they had all tangled together into a single inarticulate mass. There were few days I didn’t break through into tears while I bent over my notebook at that corner table in the back of the cafe.

In the earliest months of my writing practice, I was often rigidly and “logically” truthful. I froze often during my writing sessions, straining hard to get every detail right so my stepfather could not accuse me of lying (should he ever come to read what I wrote—and, of course, I assumed he would; up to that point, he’d had access to every single aspect of my being). I wanted to compile a record of his atrocities, and was beginning the work of disentangling my feelings from the so-called psychoanalytical brainwashing that was a core component of his control over me, my sister, and my mother. If he ever made good on his threat to have me killed for leaving his bed, I believed someone would find this notebook and finally know who I really was. In those early years, as much as for any other reason, I wrote to survive my death in the form of a final, true story. I had told so many lies—I wanted someone, in the end, to know What Really Happened.

Continue reading →

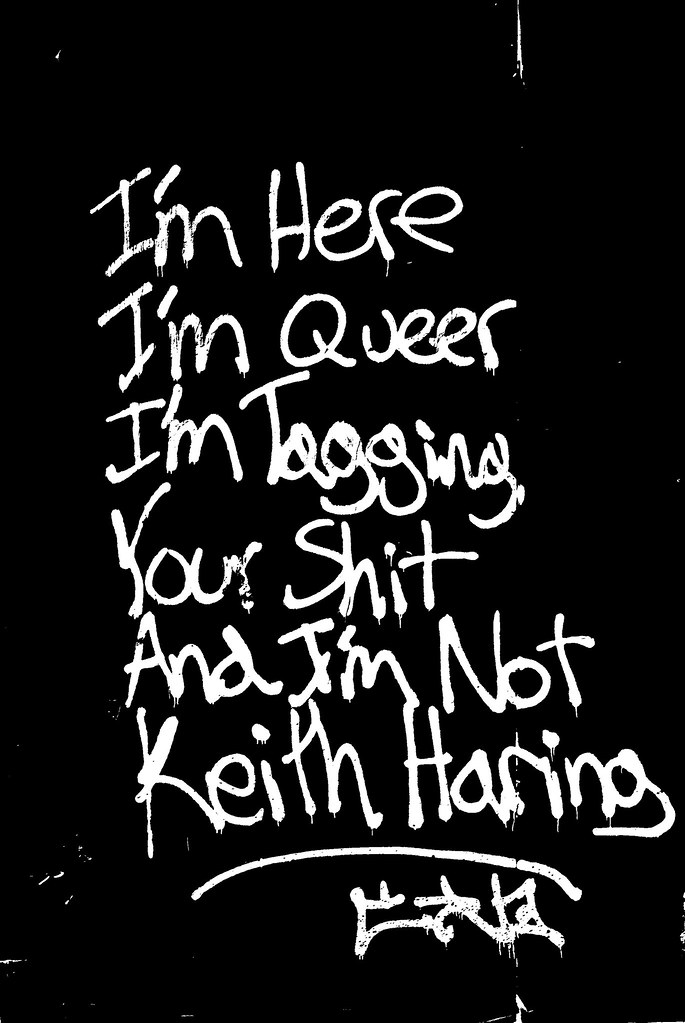

I remember when my friend Sinclair Sexsmith’s book Sweet & Rough came out; they talked about putting together a blog tour to support the book and to get the word out. I loved that idea — a book tour that involved no travel whatsoever! A chance to connect with new readers and fresh communities, chat with smart bloggers, share blog love, all while also getting to sleep in one’s own bed and not have to navigate yet another airport security line (huzzah!).

I remember when my friend Sinclair Sexsmith’s book Sweet & Rough came out; they talked about putting together a blog tour to support the book and to get the word out. I loved that idea — a book tour that involved no travel whatsoever! A chance to connect with new readers and fresh communities, chat with smart bloggers, share blog love, all while also getting to sleep in one’s own bed and not have to navigate yet another airport security line (huzzah!).

Jen & the Writing Ourselves Whole book are headed your way!

Jen & the Writing Ourselves Whole book are headed your way!