In Tuesday’s post, I said: How we tell our stories matters. The words we use for our stories matters. The metaphors and symbolic language, the imagery – all matter, all influence how we perceive ourselves, our bodies, our physical being, our agency, our history and our possibility.

In Tuesday’s post, I said: How we tell our stories matters. The words we use for our stories matters. The metaphors and symbolic language, the imagery – all matter, all influence how we perceive ourselves, our bodies, our physical being, our agency, our history and our possibility.

For instance, consider the story inside the word broken as it gets applied to survivors of violence. Broken is commonly incorporated as a metaphor into survivor stories – he left me broken. He ruined me. She left me in pieces. He tore apart my soul.

I climbed into this fragmented narrative, this narrative of fragmentation, when I began to identify as an incest survivor. Identity is a story: we don’t just take on a label when we identify as something, we take on the narratives that accompany that identity – we have to interact with that identity’s story. The incest/trauma survivor story contained these: “broken, ruined, dead.”

These are powerful phrasings, necessary to use to describe how the body feels, how the victim feels, how the raped child feels when she is violated by someone neat to be a protector, when she is physically and psychically assaulted, then silenced, shamed and threatened, then psychologically tortured so that she will comply with the abuser’s demands of silent complicity. We need a brutal narrative to match the brutality of our inner experience. We need a story that will wake people up, we need a story that will make standers-by understand why we need help. We are attempting to counteract and supplant the other, deeply entrenched stories: the child is the parent’s possession to do with as the parent wishes; children often lie and are not to be believed when they say their parents or other adults are hurting them; child abuse is a family problem and outsiders should not intervene; children often invite sexual acts; America puts women and children first – those stories hold powerful sway, culturally. It makes sense that with the rise of an Incest Survivor advocacy community, we would reach for language as incendiary as the experiences and silencings we suffered through: he might as well have killed me; he left me for dead; I felt like a ghost; I didn’t exist anymore.

As I came into an Incest identity, I latched onto the story of broken: And the more I told the story of how broken I felt, the more the story of broken is what I inhabited.

Broken was big enough to explain how I felt. Broken was also irreversible. A shattered vase might get glued back together but you can always see the cracks, the scars – and that vase was now weaker, easier to break the next time. We were broken and proud of it. Fuck you, we said. We might get better, but we were never going to be the same. He ruined us. He broke us. He stole our childhood. He stole my adolescence. He broke my sex and now I would never be normal.

These stories express our extreme disenfranchisement from our own agency. And we tell them over and over and over – and, each time we tell the story, we deepen its neuronal pathway inside us, making it easier and faster for us to tell again the next time.

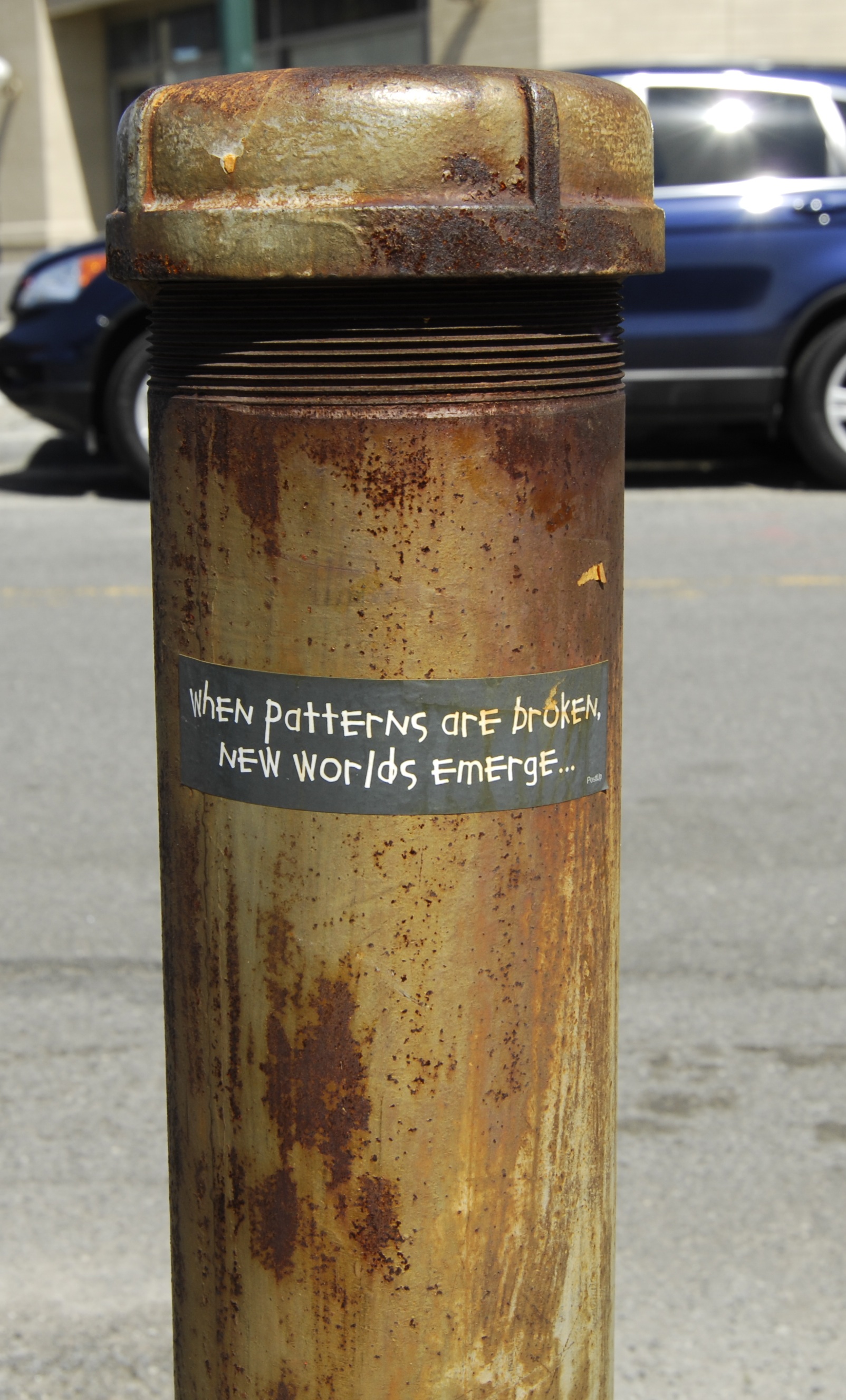

Just a few years ago, I began to question: What if that story was a lens that I was looking at my experience through? Certainly I’m using broken metaphorically, to express my sense of internal fragmentation, and of not being a normal and regular (which, my necessity, means unbroken and whole) woman. Aren’t I?

What if there was another story, another lens I could look at my experience through? What if broken didn’t have to be my name? What if I am whole, my sex is whole, my complexity is whole? What if I struggle, still have questions, but am whole, intact?

What if I could tell a different story?

“The truth about stories is that they’re all we are.”

Taking a stand against a cultural story and meta-narrative is resistance work, builds muscle.

In learning to live outside the lens or silo of Broken, I am flung (if I’m not careful) headlong into the relentlessly cheerful Gratitude story: whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

What if I didn’t want a cultural narrative, a grant application anecdote, a Hallmark card, a cup of soup for my soul? What if I was ready for a less-than-simple story, something more complex, more complicated, more real; something less pithy, less easily told?

In our survivors writing groups, this is what we hold open room and hold out hope for – the messy story, the fragmented telling, the rape story with jokes and laughter in it, the story of the loving parent who put his hands inside his child, the story of turning still for support to the mother who abandoned you – the stories that friends, surveys, some therapists, family, nonprofits, social workers, activists and advocates have a hard time hearing (literally comprehending) and holding because these stories don’t match the language we have acquiesced to as a culture: ruin, devastation, dismal, hopeless, broken.

Our human, lived stories are more complicated than one lens can reveal.

Outside of one story are a hundred other stories. Outside of Broken is frightening, still – I feel uncontained, sprawling. I also experience myself as having greater agency. Not broken or unbroken, intact and imperfect. Wounded, sore, struggling, whole. Human, like all the rest of the humans around me struggling with something.

Thank you for the stories that have carried you this far, and for the stories you are beginning to question and upend. Thank you for that risking. Thank you for your words.

3 responses to “questioning the broken story”