The media are not done using Robin Williams’ death to flesh out the little segments of so-called information that they like to provide between commercials, but his name is mostly out of the headlines, out of the 24-hour news cycle, and has moved into the next circle of news, the more in-depth and thinky pieces, the long opinion pieces, the actual tributes. But do we have time for these? There’s so much information to get to — our social media feeds, the top-of-the-hour bad news headlines on our at-work radio stations, tv blaring at us at our coffee shops, at the gas station, to say nothing of the tv for awhile after work (thinking it will “help us relax”) — how do we have any kind of intentions at all about what we’re taking in? How do we integrate the information shoved at us?

The media are not done using Robin Williams’ death to flesh out the little segments of so-called information that they like to provide between commercials, but his name is mostly out of the headlines, out of the 24-hour news cycle, and has moved into the next circle of news, the more in-depth and thinky pieces, the long opinion pieces, the actual tributes. But do we have time for these? There’s so much information to get to — our social media feeds, the top-of-the-hour bad news headlines on our at-work radio stations, tv blaring at us at our coffee shops, at the gas station, to say nothing of the tv for awhile after work (thinking it will “help us relax”) — how do we have any kind of intentions at all about what we’re taking in? How do we integrate the information shoved at us?

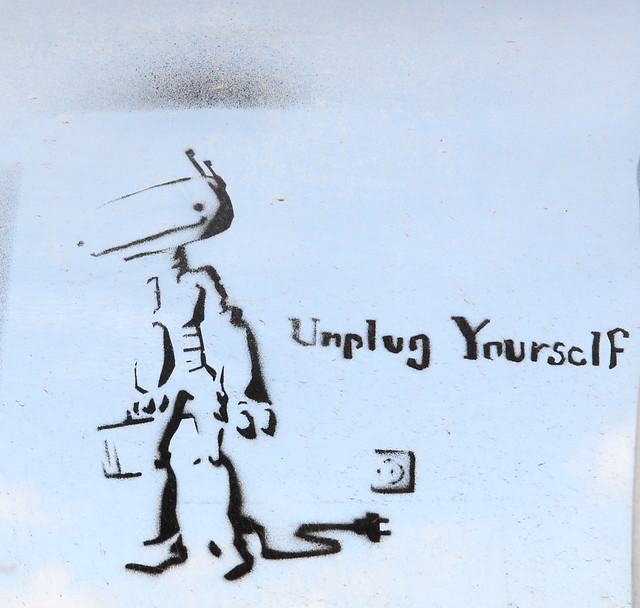

We can’t, of course, while we’re standing in the flood trying to keep our heads above water. The information simply comes at us too quickly, intended to keep us in a state of overload, making us easier to control through our undirected rage, depression, or apathy. We have to choose to step out of the information pipeline and unplug.

After spending a couple of days talking about Robin Williams (an enormous amount of time, given how much ongoing attention most news stories get — including Obama’s recent decision to send drones into another country to drop bombs on the people, fingers crossed that we will get the people we’re targeting with no “collateral damage”), we moved quickly on to the next celebrity death, spent a few minutes thinking about the horror of racist-policing practices in Missouri, and then switched to sports. This is what a strict, regimented news cycle will do to you. I often wonder about the well-being of newscasters. What is it like for them to allow these words, these stories, to be carried through their bodies and into the world, over and over, every day, for years? To have to articulate a gristly murder or the horror of genocide, then, read an upbeat, human-interest, or sports-related story, as though these two things made sense being in such close proximity to one another?

In the day after Robin Williams died, I was listening to late-evening BBC radio after a writing group. When I tuned in, the announcers were describing what was known about the entertainer’s death. I was thinking about how concerned the announcers sounded, how involved in the story. And then, without missing a beat, one of them said, with a gleeful tone, “And now it’s time for Sport!” turning the mic over to whoever it was, and the sportscaster had to come in with his headlines about what was going on in the world of football, as if this were a natural transition. It’s not at all unusual to hear these kinds of juxtapositions, and I wonder how newscasters train for the emotional work that is required of them: convey sadness here, transition rapidly during this two second breath, then convey excitement and jocularity as you say this part. How do they hold the stories in their bodies? How do they hold the apparent lack of empathy?

How do we? We’re the ones listen to news presented this way, and this is how we learn to take in information: the terrible and the banal, all at once, given the same weight and measure (not to mention, of course, the stories we know about that never get reported on the news at all). If we watch broadcast television or commercial video streams, we are likely to see images of violence abutted up against images of people behaving ridiculously– say, a commercial featuring a man wearing a clown head right after a commercial showing us strewn bodies or a gun battle or a seduction scene. Now we get to have the same sort of cognitive-dissonance-inducing information collocation in our social media streams. Americans learn to weigh all of this information the same. I am not telling you anything new. I’ve just been noticing it, feeling the madness an information-acquisition practice that we have to learn to take care of ourselves around.

In the face of rapid-fire images and stories entering our consciousness every second, how do we tune in to our empathy, our capacity for vulnerability and connection, while also not feeling wholly drained and depleted?

Last weekend I had the very good fortune to be in Southern California for a couple of days with my sweetheart. I spent an awful lot of time in the sun (all sunscreened-up, don’t worry), in the pool, or in the ocean. I read novels. I read a magazine that focused on the various cuisines of the Indian subcontinent. I avoided my technological devices. During breaks like this, as on most weekends, I tend to stay away from email and other social media. I listen to the radio much less often. I breathe more deeply, and notice how my sense of the psychic space around me expands. My attention span lengthens. I’m able to engage a thought for longer than a few seconds. Not only is this what my body needs, what my soul needs, it’s also what my writing needs.

Of course, there were newspapers on Saturday or Sunday morning, yes, that we could read or not. It was there, in a newspaper headline, that I learned that our Nobel Peace Prize-winning president had again decided to allow bombs to be dropped, using unmanned drones, on the people of a foreign country. I did not read the news story accompanying this headline, only felt the heartbreak and a deep sense of — not inertia but what? Futility. What difference could it even make to get angry? The anger doesn’t make any difference. Conservative or ostensibly-liberal president, same outcomes: endless war (thank you, President Bush). And yet our congress intends to sue not the man/administration who got us into an undeclared war on the rest of the world, but Obama, for overreaching his powers. It should be astonishing, but instead the news washes over me, leaving me with a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach and a deep sense of my utter powerlessness to do anything to change anything about how our country runs and runs over so many, here and abroad. That sweet sense of expansiveness contracts again, consuming me in a self-protective shell.

Immediately I am enraged. Why is our country like this? I want to be hopeful that our politics, our foreign policies, our American engagement with the rest of the world could change from one of dominance and power-over to one of collaboration and cooperation. But it seems not just hopeless but ridiculous to want this — I feel like a stupid hippie, and notice how deeply I’ve internalized that mainstream American judgement of anyone who wants to stop the bombs. I thought about that bumper sticker, the one that reads, “It will be a great day when our schools get all the money they need and the air force has to hold a bake sale to buy a bomber.” What if that were the country we live in? But we don’t. We live in a country that cares more about property and prowess than people. Our politicians say that they are working for the people, trying to make a better world for the children of this country, but we know better. They might want things to be better for their children, but that’s not even remotely the same thing as doing the work to make the country more hospitable for all children.

My breath begins to come more shallowly and I feel the warm and inviting waters of ennui rise up around me. How can anything anyone does make any difference? After many years involved in social change work, I come up into this question often. Nothing any one of us does will be enough to change everything. Why keep breaking ourselves open, walking with nothing but our own and other people’s pain, when those in power have it all?

This apathy is easy to get lost in, and I remember that, just for this weekend, I’m turning away from the newspapers. My sweetheart and I took long walks on the beach. At sunset one night, we stood on a cliff and watched a pod of dolphins breach and leap. I spent hours floating in the beach-side waves, looking down at small pods of fish beneath me, or gazing at the sea lion sunning herself on a rock nearby. Little by little, the tension in my shoulders relaxed again. I took deep breaths and let the sea carry me — so generous, this willingness to hold our human bodies, when humans have done so much damage to her.

On our last morning, we headed to the beach for our long morning walk and were met by a man wearing a khaki green outfit who asked if we were there for the release. Yes, absolutely, I thought, and then realized he maybe meant something besides simply release in general, and asked what he meant. “The sea lions’ release.” Then he looked at us quizzically. Didn’t we know? Two sea lions had been brought in to the Pacific Marine Mammal Center, badly underweight and in need of care. The volunteers at the center had worked to rehabilitate the young animals, and they were now ready to go back home.

We took our walk (stopping to admire the crashing waves, two more breaching dolphins, and some young artist’s line drawing in the sand of an ejaculating penis) and returned to the release site just in time to gather up with the observers (including members of a girl scout troop who had sponsored one of the sea lions’ treatment and rehab— thank you!). A couple of golf carts brought down big dog crates, each one with a young sea lion inside. The crates were removed from the carts and set up on the beach so that they opened down toward the water. A volunteer asked us to stay quiet until the animals reached the sea, so that they would not be more scared or confused. And then another volunteer opened the crate gates, and we waited. The sea lions poked their noses out, testing: do we really get to come out now? They took their time, inching forward, until they were sure that no one was going to stop them — and then they raced down the beach to the water, seemingly so joyful when they hit their home and began to cascade up and down, riding the same waves that had cradled our own bodies. They pushed through the water, and we the gathered humans cheered, watching them as long as we could, until their forms disappeared into the grey.

I wept as I watched them go (and again when I watched the video this morning), so grateful they were home, and so grateful for the volunteers’ hard work and emotional labor. What a thing, to work so hard with an animal and then watch it disappear.

What a thing, to be reminded that we humans do have the capacity to care so deeply for one another and for other beings, if only we can allow ourselves to be vulnerable enough to show it. To have the seduction of apathy and ennui and easy sarcasm and irony challenged in this way. Real change happens when we are real with ourselves and each other, when we risk unplugging ourselves from the information onslaught long enough to remember what authentic human embodiment and connection feels like.

This is what I have today. Keep writing, and talk to the animals, too, whenever you can. I think they help us learn better how to be human.

One response to “unplug”