This is a Monday morning, with roses in it, and burning-off clouds, and a puppy who has just learned to swim. This is the day after Father’s Day. This is the cool breeze that creates a confluence of culpability.

This weekend I got the new Kent Haruf novel, Benediction, and, in starting to read, returned to the world that is the place that my father is from. He wasn’t born in the High Plains of Colorado, but in the fertile land of middle-southern Nebraska, but it’s small town midwest living just the same. Reading Haruf’s setting and characters, I meet the voice and the cadence of the people I am from, and I meet all the layers of things a generation of folks never wanted to have to talk openly about: abuse, illness, homosexuality, love.

The people I come from show love through acts — they spent a lifetime working harder than a human should have to, tilling soil, tangling with weather, worrying over futures and grow rates and cattle prices; cooking meal after meal after meal, sweeping the same sidewalk, the same front porch, the same kitchen floor, day after day after day. These were acts of resilience, acts of human do-ing: what you did showed how you felt. Why is there any need to say it? Words were just words — it was what you did that mattered.

And if you didn’t say a thing, maybe that thing would un-be. If you didn’t talk about it, maybe it wouldn’t be true. The people I come from will welcome anyone with all of their arms open, as long as everyone agrees not to say aloud what we are all uncomfortable with.

Why do you have to say it? Why do you have to be so brazen? So vulgar?

How can this message come through so clearly when the words are never spoken?

My father comes from this place, this language of action, this complicated relationship with saying and silence. and thus, so do I.

Then, as a teenager, abused by a stepfather who was also a therapist, I was indoctrinated into an overabundance of words: words as deluge, words as battering ram; words as hailstorm, tornado, blizzard.

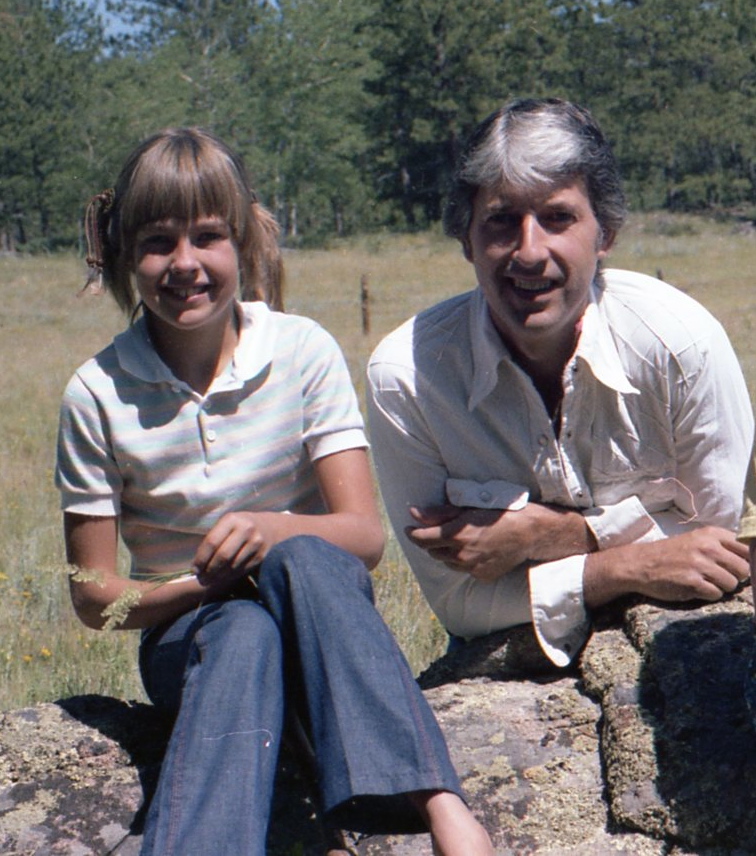

My father didn’t know how to interact with language in this way. He lived in another town while I was being drowned in my stepfather’s way with words. For so many reasons–the things unspeakable, the things overly spoken– my father and I lost the ability to speak to each other. We had no common ground in our present tense. We spent years talking about Before, unable to find shared language for our Now. Visiting with my father meant trying to become again the pre-raped girl that he’d parented on a day-to-day basis. The currency of our visits was “Do you remember?” The change was in tears, in apologies, in the spaces around the words.

Fathers and daughters–fathers and their children–often feel that they speak different languages. Ours is not a unique circumstance, I know. When my father was a young man, he tried to use the new languages he was learning to communicate differently with his own father, and found that effort — well, if not futile, then extremely challenging. Parents can’t always find their way into the languages their children discover and create in order to save themselves. Is this an everyday pain? Is this an ache we all just learn to traverse if we are going to have any relationship with our parents at all?

Yesterday I called, but I didn’t reach him. I left a message saying happy Father’s day, I hope you are having fun, here’s what I’m doing today — well, have a good Father’s day, and I’m glad you’re my dad. I didn’t try to call him again, or text. I didn’t think ahead to send a card, take some action that would show that I was thinking about him, even though I think about him every day.

I use words altogether more than actions with my dad. And yesterday I said aloud to my sweetheart, I wonder if I will ever stop punishing my father — punishing him for not being able to hear what I wasn’t able to say, punishing him for still inhabiting a landscape and relationship with language that is utterly foreclosed to me now. Punishing him for not opening his mouth wider, for not yelling what his daughters couldn’t even breathe, for being of a people who never yelled at all. I wonder when I will stop punishing myself by denying myself a fuller relationship with the man who taught me about the power of humor, about music and song, about the layers of hope that language can bring. I wonder when I will forgive myself for not being able to communicate with him in such a way that could have “saved” me and my sister. I wonder when I will let us be exactly who we are and decide to learn and trust what shared language still threads between us — terrifying, tender, broken and true.

This is my father’s day write. What does yours look like?

Big love to you today, you who are in the heart-achy aftermath of Father’s Day. Thank you for your spaciousness with yourself. Thank you for your words.