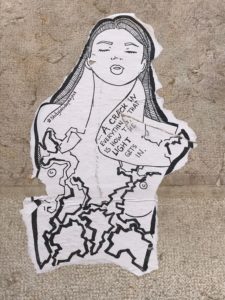

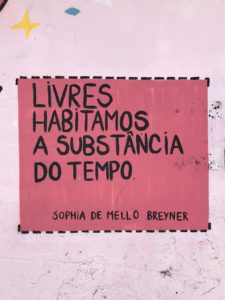

This is a photo I took in Lisbon; part of the #shitgirlsdo project

… or “Yes, we live in patriarchy, and women have been telling you forever that they’re being assaulted by men from infancy through childhood, into adolescence, all through their working and mothering years and all the way up until they die, thanks for finally listening I suppose now you want us to give you a medal”

(This is very long. All summer I’ve been repeating to myself that I can’t write, I’m blocked, I sit down and nothing comes — but the truth is, I have been writing, getting words on paper, struggling through depression and with a feeling of complete helplessness in the face of this current cultural conversation that has been so innocuously labelled #metoo. So this morning, after waking at 12:30am, once again unable to sleep, I decided to combine the morning writes I’d already typed up, and realized they served as a kind of back-to-school essay: “What I did this summer.”)

June 13

Last night I tried to get inside what has felt like enervation around writing. I sit down to write, especially to blog, and all the energy just drains out of my body. I get tired and then I sit back and look through the sheer brown curtain covered with white circles, I look out to the backyard, the brown fence, the ivy climbing the brown fence and the treetops above the fence, the eucalyptus beyond, and then the white that is the sky. I look out and my mind goes blank like the sky, goes white like that, goes empty. I try and think about what point it makes that I’m here doing this.

Lisbon street art

Type one sentence then stop. Type one sentence then stop.

Look at the candle, look through the film of the curtain. This room is full of books. Full of possibility, of the material I have surrounded myself with for a lifetime. I try and understand it, this sense of not having anything to say, maybe not being able to get my mouth my words big enough to encompass what needs to be said.

It’s not that there’s nothing to say, but that there’s too much. Do you feel that way sometimes, too?

It’s not that I don’t want to know these stories of violation, it’s not that I don’t want to hear about the crimes. It’s something about the way they are reported. Every time we’re supposed to react with shocked surprise. The media treat each incident like it’s unique, disconnected from the larger society or anything that happened before.

The headline reads, “Sexual Assault on School Campuses Has to Stop,” as though 1) that wasn’t obvious, and 2) it only needed to stop on school campuses.

The headlines are meant to do a job. They are meant to call your attention. So they must use this language this energy this sense of breathless astonishment. Each news story must be about something new. So we are hearing about assaults on college campuses and a culture of sexual violence at workplaces as though they are somehow not wholly related, wholly interwoven with one another. We are hearing about sexual harassment as though it’s somehow separate from the culture of pedophelia in the Catholic Church. We are hearing about the men who excuse the violence of other men in workplaces or on college campuses or in doctor’s offices or in professional kitchens or in Silicon Valley or in philanthropy or in sacristy or a schul or in sex-positive communities or in social change communities as though it’s not wholly related to what it means to be a man in cultures around the world. But those of us who have lived through it know that it’s all of a piece. None of this is unrelated.

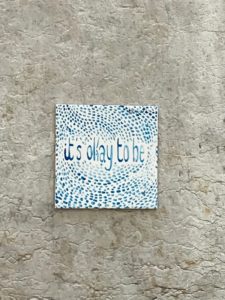

Lisbon graffiti

If this were a movie about a renegade virus, about the fear and panic around an outbreak of a disease, the scientists would have a map and they would be coloring in all the different places where outbreaks had already occurred. On the map showing outbreaks of sexual violence, there wouldn’t be any part of any map that wasn’t colored in. But we pretend like each incident reported in the news is a unique and disconnected site of outbreak. But no. They are all sites of the same disease: the sexual assault of women and children, the assumption that women’s bodies and children’s bodies are available for men to take and use as they so desire. Because we as a society have told men that they deserve this access, that they are the strong ones, they are the powerful ones, they are the ones who can keep us safe, and in exchange, we give them our bodies, and our children’s bodies. Is this the exchange we want to keep making? is this the devil’s bargain? Because here’s the heading — they aren’t even keeping us safe. It’s a bad fucking bargain. We have been harmed at their hands, in their homes, under their watch, in their churches, in their workplaces, in their schools, even in the groups that they organize to resist and create change.

If you are a man reading this and you are thinking to yourself, but I haven’t ever hurt anyone, I am delighted if that is true. But the work is on your shoulders now. What an awful thing, to be associated with such violence and harm. Don’t you want to do everything you can to change the story, to change the truth? To uproot this disease that has so taken hold?

My therapist told me last week about a personality study, which showed that men could admit to feelings or acts of sexual violence and still be deemed sane, still fall within the range of normal, acceptable behavior. (Women, on the other hand, were found insane if they admitted to such thoughts or acts). We don’t find this behavior in men insane. We expect it. We indoctrinate them into it. We tell them it’s their right.

So the disease metaphor doesn’t really work, does it? It can’t be a disease if it’s utterly enculturated, if it is part of what we call man, in this country and around the world. This behavior — the sexual assault of women and children — is not seen as problematic enough to unseat men from their thrones. You see the rise in nationalisms, fundamentalist communities, right-wing and violent belief systems — these movements are the armies that seek to keep men in their positions of power.

So what do we do? How do we sustain ourselves? How do we hold on to the ideas, the possibilities, of things changing, in the face of such horror and resistance, especially when we get triggered every time we turn on the fucking news or open any social media site? I’ve been turning off the news. I’ve been avoiding Facebook. I’ve been reading books by women, by women from around the world, I’ve been in the garden, I’ve been baking, and I’ve been eating. I sit in the sun. Every time I try to force myself into some other feeling or state of mind, I end up feeling worse — so I try to let this feeling be, I try to accept this feeling of enervation, which is actually rage turned inward.

Lisbon graffiti

She’s just inside me, barely under the surface, that twenty-four year old who was yelling at anyone who would listen about violence against women — I guess I’m surprised that there can still be people in the world who find these “revelations” to be revelatory; haven’t women been saying for generations that we have been under assault from men? But, of course, we were not believed by the men in power, we were ignored or silenced by the women too afraid to reach for change, who sought security in the cave of the monster.

A few weeks ago, I sat down with the Sunday times, and found rape in every section of the newspaper. It’s everywhere, all the time. But Jeff Sessions doesn’t want to allow women to be granted asylum here just because their husbands beat the shit out of them and their governments refuse to intervene — if we say it’s wrong there, well then by god, we might have to say it’s wrong here, and we don’t want to do that, do we?

Maybe we should see this backlash as a positive step. If we pull back and look at that larger picture, the map of disease over place and time — I read somewhere recently that if you feel the resistance, you know that you are making change. They are pushing back so hard against us because they believe that we are creating real change in this country and around the world. Of course they are not just going to lay down their power and walk away. Of course they are going to fight and say it’s righteous, say it’s god’s way, say it’s the natural order of things, make whatever frantic ridiculous excuse they can for their need to keep hold of the right to violate the bodies of women and children whenever they want to.

I’ve been thinking about how to step out of the stream of news, the reports of violence, the violence of this language (someone is brought down, a man is brought down by sexual assault scandal — nope, he’s brought down because someone finally, probably after many many years of violating others, spoke out, someone broke their silence; he is brought down by his decisions and his very own behavior).

The enervation is the other side of rage, maybe the other side of grief, too. The enervation is like depression, but without the tears.

Firing that one guy won’t make the change that we seek. Because it’s not about that one guy.

Lisbon statue; she’s directing her child’s attention to the important man standing up top — meanwhile, her ankle is still chained

June 14

I’m thinking this morning about the struggle involved in pulling oneself out of a closed system, out of a system of thought and control that’s so all pervasive it’s designed to keep you within its grasp, I mean, a system designed to confine you to one way of thought and thinking, so pervasive that it seems impossible to see it for what it is, to examine it from the outside because it seems that there is no outside from which to apprehend it.

I’ve been trying to make sense of the particular fatigue I feel around writing these days — not all writing, just writing that’s intended to participate in any sort of current cultural conversation, which has been made difficult because I feel repelled by the language being used. I refuse the terms, I don’t agree with how we are talking about things.

Yesterday it was this: the medical profession is having its own #metoo moment. It’s a phrase meant to connect to a meme, a term that’s been deemed acceptable by mainstream media because #metoo is somehow less frightening or threatening than rape culture or patriarchy. What is a metoo moment? These days, that phrase is intended to convey the idea that a person or a workplace or an industry is (finally) being called (not by victims, but finally by persons with power to impact change — the victims have been speaking out forever, have been silenced or shamed or fired) to admit to and do something to change their historical and present-day culture of systemic sexual violence. A “moment” in popular culture parlance is supposed to evoke a flash in the pan, something that’s been given its fifteen minutes, a little time to shine in the sun of our attention but will disappear underneath the Next Thing soon enough.

This is the language that gets used these days — some person or place of business or particular industry is having their moment under the spotlight, is undergoing a reckoning, is revealed publicly to be sexually violent, possibly unrepentantly so.

And we are meant to think, No way, there, too? Him, too? As though sexual violence isn’t everywhere, a part of patriarchal culture, intricately interwoven in the masculinity with which we indoctrinate our sons (and other children)? As though it isn’t absolutely everywhere, all the time?

But, “Yes, we live in patriarchy, and women have been telling you forever that they’re being assaulted by men from infancy through childhood, into adolescence, all through their working and mothering years and all the way up until they die, thanks for finally listening I suppose now you want us to give you a medal” doesn’t really make for a clickbait headline.

I turn off the news for awhile — I started doing so actively since we began hearing the story of Brock Turner’s assault and subsequent trial. Something about that incident in particular, his six-month sentence, the shit both his father and the judge had to say, that kind of knocked me over the edge of hope. I kept working and writing, I kept believing and supporting survivors, but I began to pull in. I couldn’t respond in public writing to that particular story, even though I felt like I should somehow. It happened right here in the Bay Area, it was my backyard, it was a college-educated young man at a progressive school, a young man raised after Antioch, raised, I would have thought, with lessons about consent and respect, raised with the message that real men don’t rape. But it didn’t matter. This progressive education, all our skits and writing classes and rap sessions didn’t do anything in the face of the matterhorn that is male privilege and patriarchal entitlement. He still got the message about who was important and who wasn’t. And his father and the entire judicial system backed him up, when the time came.

So what could we do? What was I doing? What difference had any of my work made? Young men are still being trained to rape as a matter of course, as a part of their passive education. They are still getting the message that It’ll be ok if they “slip”—they’ll be protected, since they’re the ones who matter. Even as we claim to be teaching girls that they have power, they are strong, they have a voice, they get to use that voice. So now we live in a world in which exists a subculture of men who are murderously enraged to recognize that women have agency and might say no.

After awhile I turn the news back on and immediately implode with resentful outrage upon hearing/reading another more story about another more man violating many, many women and/or children that is reported as though I’m supposed to be surprised to learn this information and am supposed to see th

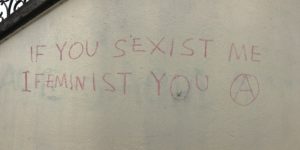

Lisbon street art; from #shitgirlsdo project

is man as an individual problem (maybe mentally ill) and not another datapoint in a worldwide reality, just another instantiation of patriarchy, another man just doing what he was raised to do (and had been told, directly and indirectly, for years, was perfectly acceptable).

The words we use, the way we talk about a thing, impacts the way we understand that thing, impacts the way we perceive it, the way we can know it. When we say, “Oh, that guy got caught up in the #metoo movement” or “he was felled by a sexual assault scandal,” all responsibility is removed from the hands of the abuser. It wasn’t his actions that brought him down, it was this movement, it was these feminists, it was those women, it was something outside of him. That language matters. It furthers the narrative that we are (already, after about ten seconds) taking things too far, casting too wide a net (because this is about nets and capturing and we’re supposed to see most of the guys complaining as innocent little dolphins caught up in the tuna catch, as opposed to members of a system from which they have benefited since birth, whether or not they have actively raped a classmate or sexually harassed a coworker).

I have been accused now and again of seeing sexual violence everywhere. Surely, folks have said to me, your history and the work you do has primed you to see it everywhere. Are there some of those same folks who might want to return to that conversation now? Can we agree that, actually, I (and other survivors and other activists) see it everywhere because it is, in fact, everywhere.

How do we step to the side of this overwhelm and rage and despair and continue to function and/or get work done and/or even continue to believe that a better world is possible? I one thing that’s given me any hope in the recent months is the raid on the Chilean Catholic Church the other day — a government entity actually willing to take on the worldwide power of that institution that has caused so much harm and damage around the world for hundreds of years. That news gave me a little twinge, a little flash, inside, of “maybe.”

July 16

Oh, it’s morning and I’m home.

The keyboard is louder than I’d like, but the other one on the computer itself makes it difficult for me to write at all. Maybe another one, another option. What’s this place and possibility? I’m back in my chair at this desk in this basement outside these walls beneath this hill inside this forest of live oaks and scrub after two weeks in Lisbon.

Lisbon street art

It’s quiet here, and last night, after you left, I had to turn on the sounds just to get to sleep — thought that’s not so unusual when you’re away. We had seventeen hours together — you counted — between you picking me up at SFO and me dropping you off there again. I cried when I watched you go through security and head off to your gate. I wondered, is this what parents feel? What is this thing in me that has these feelings, this need to be with you? Something deeper than hunger and desire — something deeper than sex. Your face appeared from behind a group of travelers when I came out of the gates to the waiting area, not having had to go through customs when getting back here because we’d done it already in Canada, in Toronto. I hurried out, once I realized, I walked faster, almost trotting, not quite running, let’s not be ridiculous. I scanned the place for you, looked int he seating area, looked up the aisles from which you might be approaching — I was getting out so much sooner than either of us had thought I would. But I didn’t see you and I figured you were still parking. I looked then for a place to wait, maybe a place with a cup of tea. I hadn’t slept, I was fragrant with sweat, with plane smells, with travel, with the dust of now three different countries on my face and clothes. And then the group of travelers walked on and there you were, leaning against a railing at the bottom of a flight of stairs,. in your black t-shirt, watching me with your side smile.You didn’t move. You were waiting for me, you were patient. You let me find you with my eyes.

It’s not that I didn’t want to make new friends or meet new people while I was at this writing workshop— it’s that I missed the people who know me in my bones already. Who hear the layers of me when I speak, who know my undersides and curves and nuances. Is this a new feeling? It kind of seems like a new feeling.

There are other words I’m looking for. Maybe this is a place of what love is, a piece of it — this opening to another’s presence in your life, in your skin. Maybe there aren’t really words for this thing. That’s what poetry is for. Outside the trees are just coming into view. It got to the point that I couldn’t wait to get home. Lisbon was an excellent trip, an astonishing experience, especially getting to go alone — I was hungry for that, too. I became aware, in Lisbon, that I am happy in my life so much of the time now. Could that be true?

Here is the bird awake at 5:30. These mornings in Lisbon were met with voices, people passing by along Rua L. S., still drunk or just awake, maybe hollering at someone inside the building across the way as the construction work got started. Mornings meant cool air, mostly clouds, and the birds, swallows mostly, but pigeons and seagulls, too, calling into daylight, calling the day. I sat for little bits on the terrace, looked over to the Taugus river and the bank beyond, but mostly sat inside, away from the voices, from the wind or the sun. It’s a strange thing not to wish to be back there, not to wish to be away from here, not to wish for something different from what I have and am in my life.

Lisbon graffiti

This is a new thing. All weeks, those two weeks, I felt grateful that I had lived this long to get to this place of possibility — traveling with a desire for home.

I loved being there, being on my own, walking where I wanted whenever I wanted. I loved all the discovery and possibility. But I got tired, too.

I met people in Lisbon, at Disquiet, but spent very little time with others. I had a couple of meals with other people, maybe just one, two, and coffee, and went to workshops and some readings and a couple of the gatherings, but the gatherings at the miradours (and especially, of course, at the bar) were about drinking; there was the open bar at the embassy, the wine receptions — these were about gathering over alcohol, helping to ease the nervousness, something. What happens when I spend time with people who are drinking hard is that I feel farther and farther away from them — like they are at a party I can’t attend anymore, they are going off to their part of the world and I can’t join them.

What are you drinking, they’d say. Tea, I’d show them, And they’d nod and smile and say something about how healthy I was, how smart.

Of course I feel like I missed out — those are the places where the connecting happens, the deepening, the conversations and openness and curiosity and revelations, the mutual riskiness.

I took pictures and shared them with the family and made little notes and comments so I could share what I was seeing and experiencing. Now I am home and it’s quiet, there are no shouting-singers, no drunks outside the window, no music from the bar (which was mostly quite nice, in all its variations), no construction noises, no trucks or motorcycles or foghorns or dogs barking (at least not right now). It’s foggy outside. Sophie andI will go to the park and walk, and I will take out a notebook and try and find words for what I want to say next, what I want to do. The novel, the workshops. This was a good transition, this time in Lisbon.

In Lisbon I moved every day, nearly all day — 6, 8, 11 miles walking. climbing. Last night out with Sophie I felt the impact — sure, we can walk down the trail and then come back up the hill. That will be no problem. But it was late and I was in the wrong shoes so we only went down part way and then came back — but maybe later today. Maybe this evening. I like this office space and this quiet. The house feels enormous after the studio with the slanted roof, ceiling, on which I ith my head so many times I think the bruises are still healing. Our kitchen, the fact of the dishwasher and washing machine, the fact of the space outside, how good it feels to move.

August 14

Lisbon street art (don’t do it, girl child — kissing the frog is never worth it)

I’ve been trying to get to the page all day. I’m trying something else now. Now I have the tv on and I’m at the couch and I’m listening, the upper mind occupied. I decide I’m going to go to a cafe, then change my mind. I get set up at the desk downstairs at 6, and get as far as naming this document, and then I start scrolling through the documents from around this time in 2010 and 2011, revisiting who I was.

I have tea, the notebook and pen. I sit down and all the old addictions scream at me — or do they scream? They whisper. They are simple and comforting. They talk to me like they make sense, they are easy, they are — how do I say this — they are my friends. My long-term companions. They sound so reasonable: You’re going to be fine. Don’t worry about it now, don’t get stressed. You can do that later. You’ve got so much time. So much time. Go ahead and eat something now. Open up Facebook, check out what’s happening in the world.

What is it that keeps me from sitting down at my desk, sitting down with the notebook, pushing in? My throat speaks up now. Let’s eat, it says. There’s food upstairs, right? There’s cereal and the rest of the galette that mom left, there are cookies that Ellen doesn’t want, there’re tortillas, I could make quesadillas, make popcorn. Eat eat eat. watch tv. I come downstairs, shut the doors, keep the light out. It’s grey outside, but the sun is coming — isn’t it?

I wanted to get started today, I wanted to come back. I wanted to find a way in, to start to explain where I’ve been, why I haven’t been writing here. Why I haven’t been seen, why I’m out of view. How much longer do I have to wait? I read through the morning writes from August, September 2010, and that woman was wanting out, imagining a long road trip, a house in the country, someplace quiet, isolated, someplace small, inexpensive, someplace I could afford — me and Sophie, just us, we would make a space just for ourselves. I read through those old writes, journal entries, longings, and I find that I have so much of what I wanted then. I was asking myself, over and over, if it made sense for me to feel the way I did, if it was normal for people in relationships to dislike each other sometimes, or even often, to have moments (or long stretches) when they didn’t communicate well or at all. Now I’m on the couch, and Sophie is at the other side of the couch, she’s on a warm blanket, she’s folded into herself, we are together.

What’s coming? The parole letter. Am I afraid that I won’t say enough, that I won’t say it right, that I won’t have the words. Don’t I want everyone to know? How do I say it?

On August 29, I’ll be in a room at the Community Corrections Center in Lincoln, NE, asking the parole board not to grant parole to the man who abused me, my sister, and my mother, and harmed countless other people in the community,

He’s been given a parole hearing, which means he’s being considered for parole. Which means he’s been deemed — what? — worthy of early release. Rehabilitated. Safe enough to be released into the community. This man.

He’s also been moved to a community corrections facility — from which he may be allowed to leave, work in the community, without regular, consistent supervision (though he may have to wear an ankle monitor, which would give us a little peace of mind).

This isn’t flowing, there’ s no poetry in it.

Lisbon street art

When did we learn about the hearing? February? February. My sister found the information online. Thank goodness she was monitoring it herself; the corrections department didn’t get in touch with us until June, I think. If we’d waited, we wouldn’t have found out until very close to the date itself.

I don’t have much energy for this now, Is that right? It’s not that I don’t have energy. It’s not that I don’t have words, but I have too many. Is it that I get flooded, swamped?

The popcorn is right upstairs.

I’m trying to figure out what to say, how do I know what to say to the parole board that will convince them that he should not be out of jail, he shouldn’t even be in the minimum security prison.

We learned that he had been moved to this minimum security prison while I was in Portugal; I spent several days in a panic, in a fury, in a rage. What do we have to do? What else would he have to have done to us for him to be deemed, to be seen as the threat, the violent predator, that he is?

I try to remember everything that I wanted to say, that I was feeling, the ways I swirled and fell into grief. What will it take? This man controls, threats, shames, hits, rapes us for a decade, and he’s going to get let out. Men who got arrested a few times for smoking a joint, those guys are in forever.

I keep thinking I’m going to be able to write about this. And then I get quiet inside, not cold exactly, but blank. Not shut, not stoppered, but like I’m up against the criminal justice system, once again.

The popcorn is still calling me. It gets louder. It’s not insistent, exactly, but like a presence, like it’s already in my throat. Like what difference does this make? But that’s not it — more like, you can keep going with this after you have me, says the popcorn. Even though I know it doesn’t work that way. If I stop here, I won’t start again today.

Lisbon graffiti

August 15

It’s dark outside, and I’m listening for the owls. Yesterday I got started, I was here in the morning, I was ready to write something about the hearing that I would post on facebook or the blog or something, but I stopped. I read old morning writes, I thought about who I was 8, 7 years ago at this time. And who I was was hurting. It’s exhausting to read, draining. Just leave, I want to tell her. Just go. It’s not going to get any better. The longer you stay, the harder it’s going to get to go.

Did I want to say something about Portugal, about the workshops, about what I do and why? Why is it that I’m so tired when I think about writing these days? I get exhausted, overwhelmed — why would I spell it out? Who cares?

I get so sick when I use Facebook — literally sick to my stomach. Is there another way to do it? I manage to spend time there in ways that are harmful to me. These days, when I go to Facebook, I search out controversy — not to engage in it, just to read, to immerse myself in, to bathe. These are situations in which I have some marginal connection (community, friends of friends, or old friends. people I once knew), writing vitriolically about situations or issues that matter a great deal to me generally, even though I don’t have any involvement in the specific situation. In one case, the writing all had to do about an altercation at this year’s dyke march; in another case, it has to do with a student of an old friend writing about how she felt emotionally and psychically harmed by my friend’s actions when he was her teacher. In both cases, voices are utterly polarized.. There’s a clear line down the middle between two camps, two opposing opinions, two visions of reality, two interpretations of reality — both camps/groups feel wholly in the right, certain of their point of view and interpretation of events and memories; everyone is righteous and clear. Each side is fighting the good fight, trying to make the world a better place, only speaking up the way that they are to help others who might find themselves in similar situations. Incident reports, letters to the editor, callings in, callings out: these are all intended in each of these cases, to make visible what (those speaking believe) has been kept invisible, hidden, ignored by their communities, or media, or the public at large. In both cases, there’s actual violence that’s occurred — humans have been harmed in meatspace (as we used to call it), offline; one person used their body to physically harm or threaten another body, in one case absolutely intentionally. And yet what I’m drawn into is the violence online—our language, the way we talk to each other when we know we are right, when we have a message we want to teach, when we are experts and others need educating, when we have been silenced or ignored or shamed maybe by mainstream society and we know where to go to land some punches: we look around us, to the people who were supposed to be protecting or standing beside us, to our allies (and what does this word mean today, especially in an online context?), to our communities. This used to be called horizontal hostility, punching sideways at those standing with you because you can’t or don’t seem to be having any impact at those who are standing on your head and shoulders, directing your anger about oppression at those who are suffering similar oppression to you, rather than at those who are causing the oppression.

I know what it’s like to feel so righteous, to feel so certain of my answers, of my anger.

I was thinking, while I was in Maine, about the time I spend online these days. There was an article in the NYT one morning, “The Trolls have Won,” which made it sound as if the author believed that the trolls won just recently. But I think it’s social media that did it, that gave the trolls their final bridge into the mainstream (well, that and the comments sections on every site these days). So, thank you, Facebook, thank you Twitter.

Lisbon street art

I’ve been online since 1990— nearly 30 fucking years. Once I loved it — I loved what seemed possible: the sharing of information around the world, the ability to connect with those you might never be able to meet in person, the ability to find support and resources around things you couldn’t talk about in meatspace — when I was first coming out as in incest survivor, I was terrified to go to police or therapist, I was afraid to check out books or buy them in a real store, but I could go to purely text-based newsgroups and talk with strangers about what I was going through; this was a time when it was still a sane thing to do to be anonymous online, is that how I want to say it, when being anonymous didn’t necessarily mean you were a hacker or a troll. It just meant you weren’t ready to give your name, you were afraid for your safety or your job, so you visited alt.sex.motss undercover of pseudonym, handle, just to be safe.

It doesn’t even make sense to say things are different now. It’s not even apples and oranges; this thing that’s available to me through web browser or email or app bears almost no resemblance to the place I spent so much time in the 90s – though of course this world existed then. There were trolls and what we used to call flame wars (and now call calling out or having a conversation on twitter); there were codes of conduct in every community — folks, those who’d been around longer, reminded the newbies: don’t feed the trolls. Don’t engage them. Don’t give them what they want: attention, energy, time. There have always been trolls, those folks who, in any situation, online or off, will make a comment just to get a rise out of someone, to piss people off; this is the guy who always has to play devil’s advocate in any discussion, or the woman who just needs to point out every slip up of language or terminology — I can’t take you seriously if you describe your feelings as dark, or some such.

At this point, mostly, going online feels like (I forget where I read this) walking into a public square where everyone is yelling at the top of their voice.

What is it in me now that goes to Facebook for this sort of indulgence, this sort of sticky so-called pleasure: here are people arguing righteously, shouting at people they used to call friends, allies; here we are, standing up for our people, showing off how educated, how woke we are, using the right (and right now) words to put others down, to reveal their ignorance, their backwards thinking.

The way I spend time online is taking me back to those days when I laid on the couch and watched talk shows all day, too depressed and frightened to get up, to leave the house, I watched Jerry Springer, Sally Jesse Raphael, Rikki Lake — these shows fostered the idea that we’d watch real people talk about their troubles, that they hosted brave folks who are exposing difficulties that are shameful or scary in order to help us, the audience, so that we don’t have to go through whatever it was alone. Maury — right. There was Maury, too. But after watching these shows, I usually felt gross, like I’d just participated in a public shaming or humiliation. Here were folks who’d likely been paid some small (comparatively) amount of money to let people berate them in front of an audience of thousands, at least. who revealed terrible things about themselves, who leveled accusations, who screamed at family, at loved ones, who got more and more entrenched in whatever view or opinion they’d been called on to television to defend or change. The host asked personal, leading questions, and the guests cried or grew angry, the audience grew angry or scandalized, shouted, booed, cheered —

Go back further: the stocks. The public hearings. The coliseum. Football. Rugby. We gather to bear witness to the suffering of others, not to ease their suffering, but for our own entertainment, to pass the time. To pass the time.

August 16

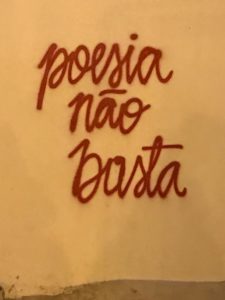

Lisbon street art; poetry is not enough

It never really gets dark here, there’s always light in the clouds from the city; on clear nights, it’s a little bit darker, but when do we have clear nights? Yesterday I took BART into Oakland, to the office. The office was quiet (mostly) and it felt good to be there. I spent hours in front of the tv yesterday; that’s going to be the name of my biography: she spent hours in front of the tv. Always the same sitcoms. The same stories, I know these shows by heart. What is it that I’m getting from them?

Why am I so quiet inside? Why aren’t the words pushing up, bubbling, now that I’m back home? In Maine, I was ready to write — I left the beach, went in to the bookstore to get work done, to sit with the notebook. But now I just feel quiet and empty. Yesterday I was writing about how terrible the internet is. A couple of days ago, I posted something about the hearing on the 29th, and I’ve had an enormous response — people from all parts of my life showing up, sharing words of concern and support, asking what they can do, telling me I can do it. I go to FB for things like this — to reach out for love and concern — and then I tend not to offer it back much, because I spend such little time there.

Two weeks in Lisbon, then three weeks in Maine. So little time in front of any screens. In Portugal, I walked — I left the tiny studio and moved my body through the city, miles every day. It was like when I first got to San Francisco, and felt too cheap to pay for the bus or subway, so I just walked, wanted to see everything, find my way by foot. If I were in Maine alone, there would be days I didn’t drive, days I didn’t leave the beach. We get in the car to drive to ice cream, some days that’s it. I drive in to a cafe for writing when everyone else is around — how would it be if I had the place to myself? Something about getting in the car, having to drive, having to surround myself that way, inflict traffic on myself, launch my body into that fray. Is it agoraphobia or something else, something broader, or smaller — wanting to be home, wanting to be able to walk to what I need, hasn’t that always been my desire? And yet I’ve never really made it for myself — maybe at Madison, that was the closest.

Lisbon street art

In Lisboa I walked. I put a book in my bag, a bottle of water, and took myself to little outdoor cafes, In Maine, when we were alone I read everyday, 10, 11, books in a week.

Am I feeling left out, left behind? Or like I’m intentionally stepping off the racetrack. I’m just not interested in keeping up with every podcast, every new show, every stream of content, Content is king, you say when I’m astonished that a network has decided to make not a movie but a tv show from one of the books we read in Maine, Sharp Objects by Gillian something — not Anderson, that’s the woman from the X-Files, a show I also didn’t watch? After we got home, we started watching the latest season of Orange is the New Black, but it was all violence immediately — guards beating the women indiscriminately, sadistically, forcing them to have sex with each other, the women tearing at each other over old injuries. Nope. We turned it off after the first episode and didn’t go back.

In the newspaper I can read about the Catholic Church and the latest revelations about their covering up priests’ abuses, violations of children. I can read about a man who shot his wife and children after a several-month-long struggle over custody. I can read about men blowing up a bus full of children, about white women calling the cops on black kids selling water, about the world’s atrocities. It’s not a thing that ends, or that’s going to end. Men are trained by other men to seek power, influence. If you are not a man that seeks power and influence, you’re not really a man. The sexual assault of women and children goes along with this, like a side car, like a carnival prize. It’s one way to display your power, to show the world that you’re a real man.

Lisbon graffiti

September 20

I was hoping for owls at this hour, but nothing yet.

I don’t know — how are you doing with this whole Brett Kavanaugh thing? Of course I’m not surprised that we, as a society, are having the same conversations about men’s violence or predatory or threatening or aggressive behavior that we had when Dr. Hill came forward about Clarence Thomas’ behavior toward her. What’s astonishing to me is that the Senate delayed the process for a single week, and are at least pretending to take this new information seriously. Take this in contrast with the response to every new revelation of shitty or sexist or predatory or violent behavior on the part of our President. (I can’t look up links to the stories right now because I will get distracted from the writing and so angry and more deeply depressed that I won’t be able to write anymore. That’s what’s happened so often over the last few weeks when I sit down and try to write something for the blog.)

What’s crazy-making are the public conversations, the constant repetition in the press of the details of his actions toward her (yes, please, say it again — there might be a couple of folks in your listening audience who aren’t triggered yet). What’s crazy-making is this sense that we’re shouting into the wind. That there can still, and it seems there always will be, be more weight given to a man than to a woman — I mean, a man’s word will be given more weight and credibility if he’s responding to a single woman (I keep saying, if you’re going to be raped or assaulted or harassed, make sure that your assailant assaults others, too, so that you’ll have others to back you up if you ever decide to go to some authority to hold him accountable for his actions). The woman is still the one portrayed as tattling, as the little girl pointing on the schoolyard and whining, It’s not fair!

What’s crazy-making is hearing folks say, over and over, I don’t know, he’s a really great guy, it’s hard to believe he could do something like this. (The subtext is, “I never saw him rape anybody; how can I believe you if I didn’t see it with my own eyes?” How many millions of people have had this thought about priests who were actively (or are now) harming children?)

Yes, the actions one commits as a young person, a young adult, matter. This is someone being considered for a lifetime appointment to a court where he will be making decisions that affect the lives of all women in the country.

Do we really need to hear the question, why didn’t she come forward earlier, over and over again? Do we need to say Clarance Thomas over and over again? *We do, actually — because his isn’t the name that I’m hearing. The name that I’m hearing on every reporter’s and commentator’s lips is Anita Hill. She is the one who carries the weight of his actions, because she’s the one who named them publicly. He gets to just be a supreme court justice. She — though she is a respected and successful law professor — gets to be the one who said those things about a man in front of Congress. When someone says, Anita Hill in the media, it’s a kind of short-hand for the whole situation: the fact that he behaved abominably towards her, he was elevated in his career, she believed that his actions in the workplace revealed a great deal about his feelings towards women, his respect for them, which would, necessarily, impact his professional judgement, and so she chose to bring this information to light. When we hear Clarence Thomas, we think, supreme court.

Lisbon graffiti

It’s absolutely not fair.

I’m still walking around in the aftermath of the parole hearing. Last month, my sister and mother and father and I all travelled to Lincoln, NE, where we spoke in front of the parole board, making the arguments that the man who had abused my sister and me should not be released on parole. It seems pretty straightforward, right? But the in-practice, the whole thing was not straightforward at all.

Sometimes you go through something very big, and life goes on as usual after it’s finished, and on the outside you look like your normal, functional adult self, but on the inside, you know that you’re not ok, and sometimes it’s all you can do to take the most basic care of yourself. Maybe you return to your life and have others to care for, a busy job, a great deal to keep your mind occupied. Maybe you don’t. I don’t. It’s been very hard for me to concentrate on much since I got back from Nebraska. There have been a couple of health crises, and of course workshops to attend to, and during those I can show up, of course. But then the workshop ends or the crisis is concluded (thank goodness), and everyone leaves and goes out into their lives and I am back in this place of stasis. It looks and feels like depression — very tired but unable to sleep well, aching body, unable to concentrate, unable to see the point in almost anything I do. It’s a deeper depression than I’ve been through in awhile, and I keep beating myself up for not being more functional, not getting more writing done, not Doing More Things. It’s all so heavy and full; everything feels like it takes twice or five times as much energy to complete.

So I make tea. I watch familiar and friendly old shows. I eat too much. I avoid email and phone calls. If I were back in school, I’d be developing or nurturing some new sexual obsession in order to take my mind off my grief and rage. I’d take myself out dancing a bunch of times — or I’d just drink too much with my friends.

I’ll write about it here eventually; the news keeps derailing me.

Lisbon street art; Google translates as “free we inhabit the substance of time”

September 25

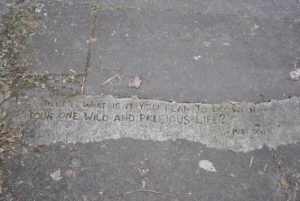

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” – Mary Oliver

I don’t know how to build this story, or make it pretty. I can’t sleep these days. I wake up in the middle of the night, try to sleep again, turn over, shift, try to go back to sleep, cant. Tonight I woke up at 12:30, and finally got out of bed an hour later. I make tea, come to the desk, light my candles, and sit down not feeling especially hopeful, just resigned. Something deeper and sadder than resigned. Something older and much angrier.

Are you taking care of yourself these days? Are you getting enough sleep, eating well, staying connected with friends, those who love you, writing or painting or otherwise doing creative work that brings you joy and opens you to permeability?

Me, either.

Last night, listening to the radio about this third — what do we call it — this third description of B. K.’s deeply respectful behavior toward women — let me give a link here, I’m not going to recite the details right now, as they are awful — I wanted to throw all the chairs off the deck. I wanted to break something big and heavy, toss it in the air and watch it smash on the concrete below. I wanted to do something irreparable. I wanted to know how it felt.

Yesterday I kept the news on while I was working — it’s been so hard to get motivated to work, and I was feeling good that I had the energy — and during the few hours those few hours, I heard, repeatedly, the details of B.K.;s assault on Dr. Ford’s and his assault on his classmate at Yale. Then there was the opportunity to listen to a detailed description of the rape of a high school girl at the hands of at least two male classmates. I declined, turned the channel, turned it off. I got to hear news anchors describe only cursorily Bill Cosby’s assaults on the one woman whose case made it to trial, but they did remind us that he has been accused by 60 women of doing exactly the same thing to them. (SIXTY.)

If I were to read the paper, maybe I would see something about the “scandal” in the Catholic Church — it’s a scandal now because people are paying attention, some handful of priests are being held to account, the church is paying some small amount of reparations, our progressive pope is having to face his own actions and inactions around the sustained and systemic abuse of children under the auspices of church and god.

The other day, I said to my sweetheart, we use the phrase “war on women” like it’s a metaphor, but it’s a fact.

We live amid men — family members and coaches, religious “leaders,” classmates, people we may have known since childhood, doctors, mentors — haven’t I written this all already? — who will, it seems, if given what they consider to be the opportunity, unhinge us from our wild and precious lives for their own momentary amusement, and then go on with their own lives like nothing happened, like they didn’t do anything wrong, like they didn’t violate the autonomy, the bodily integrity, the sovereign integrity of another human being. This begins as young as very early childhood and can continue through a man’s whole life (hello Bill Cosby), He has a system of laws and societal mores and social rules/restrictions that protect him. He has a community of men — teachers, coaches, school administrators, police, courts, classmates, teammates, accomplices, presidents — who will hold his secrets for him, support and sustain him, treat him with respect, remind him that he’s a good guy, a giving guy, remind him how much good he’s done in his community/school/workplace, who will pat him on the back and say good man, who will rally around him, who will — if she breaks his silence and tells about his violation of her— reframe the problem as hers alone. (think Anita Hill, Monica Lewinsky — their names precede the word “scandal;” Clarance Thomas’ name precedes the phrase “supreme court justice; Bill Clinton’s name preceded “president” — why don’t these men get to evoke “scandal” whenever their names are uttered, too?)

And to protect us, we women? We have a system of laws (which work very well to inhibit sexual violence, as we can see from the news.) We have rules and mores that teach us who we can talk to, what we can wear, where we can go, what we should act like if we don’t want to draw the wrong kind of attention — that is, we are trained to police ourselves, each other. We have “chivalry” ostensibly on our side, which, as we can see, has not worked to keep us safe in any way.

What have I done with my one wild and precious life? I have spent it recovering from the violence that my once-stepfather decided, over and over, daily, over the course of a decade, to inflict on me and my family. I am still in that work. My task has been to clean up the mess that he made of me. I want not to think of it, of myself, that way. I want to say that he didn’t succeed, I am unbroken, I am a survivor. And I am. But I am also irreparably harmed; his actions impact every day of my life. they have impacted where I lived, my work as a writer, my work off the page, my sense of myself and my capacity.

I have been reading recently about the uses of rape as a war crime in Bosnia during the wars in the early 90s, and the abduction and sexual enslavement of Yazidi women in Iraq. I read about the rape of Chinese women in Nanking by Japanese soldiers, and their keeping of Korean “comfort women.” Women are systematically raped in conflicts in the Congo, Sierra Leone, girls are abducted and kept as sexual chattel in Nigeria. Women are being raped as a part of the effort on the part of Myanmar’s Buddhist majority to ethnically cleanse their country of Rohingya. There is an epidemic of violence against Native women across North America, women sexually assaulted, women disappeared. Men still, in the US and around the world, even after a century of efforts to raise awareness of and criminalize the behavior (with the idea that, I guess, if it’s against the law, maybe at some point men will understand that it’s unacceptable—though, again, as we see, that hasn’t worked with rape) beat, rape, and kill the women they say they love, they tell others that they love, they pretend to love but really just seek to control (I can’t look up links to news stories about domestic violence right now, I just can’t).

Oakland sidewalk art

What about our wild and precious lives? What else had we planned to do? Does it matter to the men around us?

I am preaching to the choir, I know. I am yelling this out to the home team. We know all these things to be true. Here’s what else is true: What we are hearing about this man, this judge, this man who has been instrumental in the creation of legal precedent, who has been allowed to rise almost to the top of his field and participate in legal decisions that will get woven into the fabric of our country and history—his actions are part and parcel of this war against women. The description of the actions he and his friends are to have engaged in in Washington dc sound remarkably like the actions of Serbian soldiers in 1992.

This isn’t about a few bad apples. This isn’t about a couple of priests gone rogue, it isn’t about individual ethnic conflicts. Pull back, look at the planet from a different vantage point — I mean, consider the actions of men in all environments and cultures across the planet: men create conditions in which they can systematically make use of and then destroy the women around them. If they are not actively harming the bodies of women, then they are keeping the silences of the men in their communities who have.

On the news last night, I heard reporting of a conversation with a male classmate of BK’s — I think it was from Yale — who said he had heard the story about his actions toward the second woman who has come forward; this classmate said that the story had stayed with him; he never forgot it. News for this “friend” of hers:

1) neither did she ever forget it,

2) but you did a great job of helping BK hold his silence for all these years.

It’s that simple.

I am tired of thinking about us having to break our silences about the harm done to our bodies and our lives. Last night I said, these men walk around in our silences. They count on our silence in order to continue living their happy lives. These crimes, this shame, these silences all belong to the perpetrator.

What will happen when men begin coming forward about the actions of their colleagues, classmates, coaches, parents, friends, frat brothers, priests, mentors, and brothers? Not out of some idea of chivalry, not out of some sense of protection, but out of a sense of human decency? What will happen when those men — those men who read this and say to themselves, Hey, ti’s not all men! Hey, I’m not like that — those men who want to change what it means to be a man (look at the history of the world; rapist is what it means to be a man) — what will happen when those men begin standing up and fighting back? Whey they refuse to hold the silences, to collude with the violence, to laugh along, to keep watch at the front door for the cops or some other authority, even if they’re not actually in the room where those men are raping that drunk girl?

it used to feel cathartic to write these things. It doesn’t right now. I feel sick and still wide awake — what is sustaining me right now is the new writing I get to be surrounded with in workshops and writing groups, plus ridiculous sitcom reruns and many many cups of green tea.

~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~

7:00 am

I’m grateful that you’re out there. I know I am not alone in these feelings, in this overwhelm, in this ongoing triggeredness, in this sense of being so enraged that some days it’s all I can do just to keep putting one foot in front of the other without smashing all the furniture or windowpanes or dishes in my immediate vicinity. “Be easy with you” is, for me, difficult work these days — but I do keep saying the words to myself, a little like a mantra, and trying to let myself feel it when others say it to me — I mean, feel and trust their care and concern. I offer that in your direction, too — care and concern from my corner to yours.

Be easy with you. Your life, your living, is wild and precious. Find your way to your words however it works best for you. Please keep going — we need your stories, in all the forms in which they come into the world.

5 responses to “What I did this summer…”